Some genetic traits inherited from Neanderthals may increase a person’s likelihood of developing autism, according to new research involving two Clemson University scientists.

The study, conducted in collaboration with Loyola University New Orleans, marks the first time Neanderthal DNA has been directly associated with autism susceptibility. However, researchers emphasize that people with autism do not carry more Neanderthal DNA than others — modern humans generally share about 2 to 3 percent of their DNA with Neanderthals.

Instead, the study found that specific Neanderthal-derived genetic variants appear more frequently in people with autism than in those without the condition.

“This is the first evidence that I am aware of actually showing that Neanderthal DNA is associated with autism,” said Alex Feltus, a professor in Clemson’s Department of Genetics and Biochemistry.

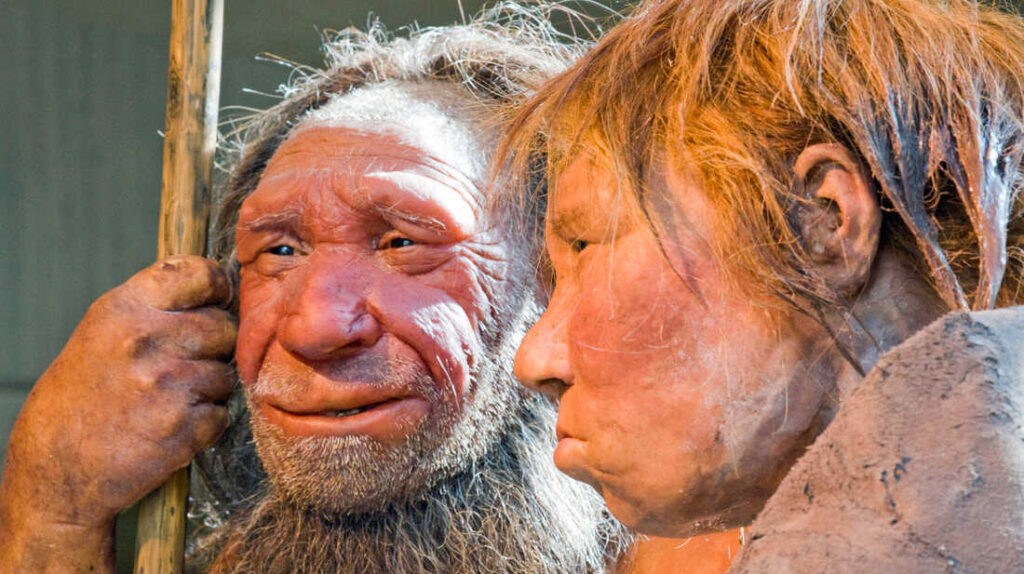

The findings, published in Nature: Molecular Psychiatry, shed new light on how ancient human hybridization may influence modern brain development and function. Neanderthals and modern humans interbred more than 50,000 years ago, leaving a genetic legacy that researchers are only beginning to fully understand.

Neanderthal DNA has previously been linked to a range of health conditions, including autoimmune diseases, depression, prostate cancer, and even protection against schizophrenia. This study adds autism spectrum disorder to the growing list.

Using data from public databases — including the Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research (SPARK), Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx), and the 1000 Genomes Project — the team identified 25 Neanderthal genetic markers related to brain development that appeared more often in individuals with autism than in ethnically matched control groups.

Still, having these genetic variants does not guarantee someone will develop autism.

“The hypothesis is not, ‘Did Neanderthals give us autism?’” Feltus said. “It’s that Neanderthals gave us some of the gene tweaks that give a higher susceptibility for autism.”

Feltus emphasized the complexity of autism as a trait, noting that thousands of genes may play a role. “We embrace complexity,” he said. “We don’t try to erase complexity.”

The research was co-authored by Loyola assistant professor Emily Casanova and Rini Pauly, a Ph.D. candidate in the Clemson University–Medical University of South Carolina Biomedical Data Science and Informatics program.

Feltus said the team hopes the findings could eventually contribute to earlier and more personalized diagnostics for autism spectrum disorder.

“We’re not just trying to draw connections to the past,” Feltus said. “We’re trying to understand how those ancient gene variations still affect us today — and how that knowledge might help us in the future.”